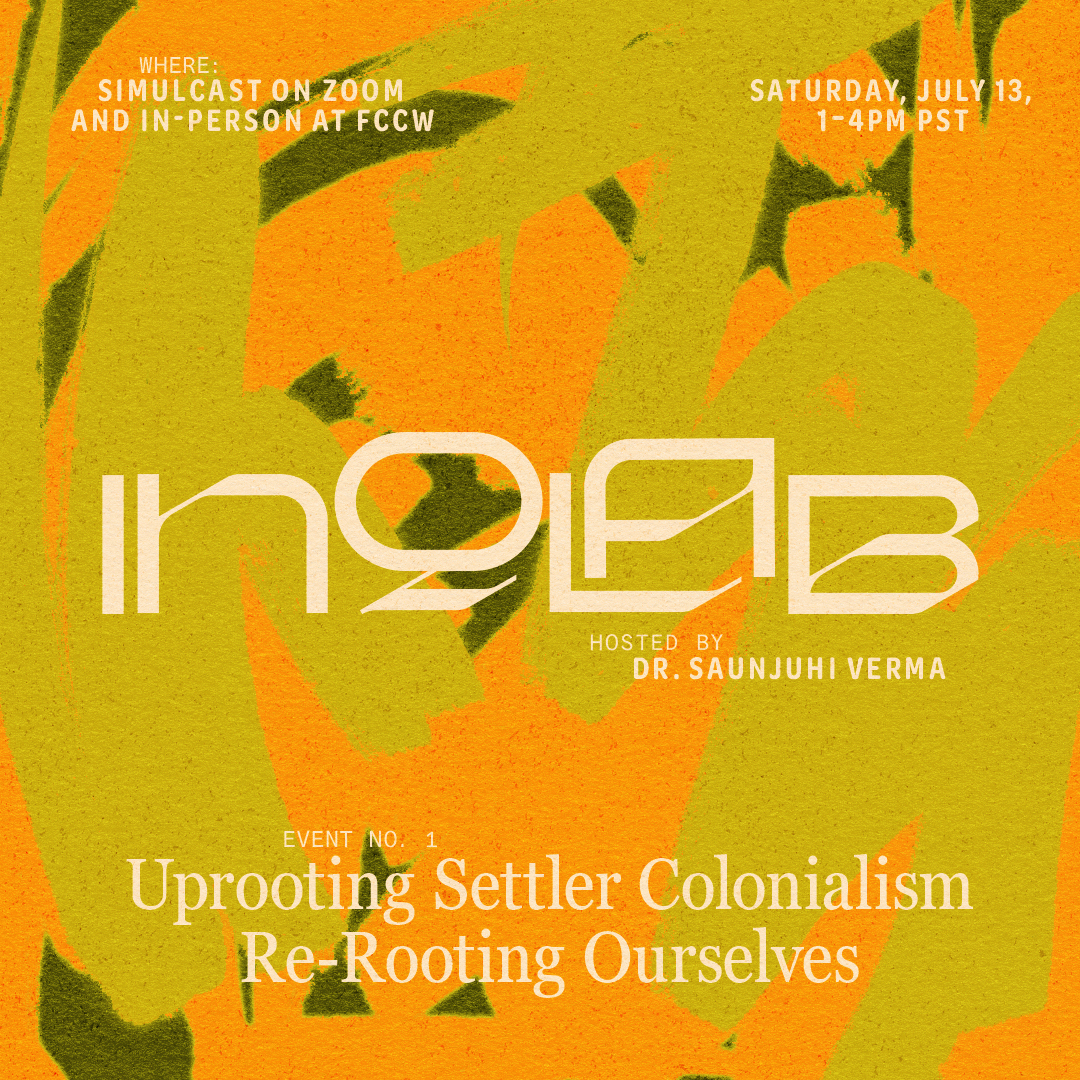

Saturday, July 13, 1–4PM PST

Simulcast on Zoom and in-person at FCCW:

1800 S Brand Blvd, Suite 111, Glendale, CA 91204

More info on finding our space here

Zoom link sent 24 hours prior

Cost: $10-20; no one turned away for lack of funds (email us at [email protected] if cost is prohibitive) — offerings contribute to our community fund which supports future gatherings and collaborations with critical partners

Starting this July, we’re inviting you to a program series called Inqlab — a monthly gathering led by Dr. SaunJuhi Verma for unlearning settler complicity and imagining radical futures.

Inqlab, which means “revolution” in Urdu, is a place where we’ll build community by engaging in political education, experiential anti-colonial activities, and experiment with revolutionary tools for change. Each monthly session will expose central organizing principles of settler colonial nation building across critical geopolitical territories, and will invite us to unravel the knots of our collective oppression, foster new modes for connection, and strategize the means for constructing a world beyond the current occupation.

The first catalyst event for the series is on Saturday, July 13, and will introduce the makings of settler colonialism within Turtle Island, now labeled United States, and Palestine, as well as legacies of resistance. The following Inqlab gatherings will explore a specific issue, like settler legal structure, colonial capital, immigration, labor, and mobility rights, among others.

As a community lab, the space will serve to understand systems of oppression while building upon modes for liberation; a creative undoing of sorts. Our political unlearning will incorporate experiential modes of embodiment that range from the whimsical to the astute. We will explore with play, through my Settler Colonialism Bingo game, reconnect with mindfulness techniques of radical listening, and engage in sowing seeds of change through the activities like Political Descendant Family Tree.

Dr. Verma will curate suggested readings for each session, which are not required for participation, and offer questions for discussion in the comments section of this post.

You can attend this program in-person in LA at FCCW or join our simulcast via Zoom from anywhere! If you can’t make the first event, we encourage you to join us for future sessions.

Resources

There is no expectation or requirement to do readings for these gatherings, but if you want to learn more, we’re sharing 5 readings in this folder:

- two excerpts from Settler Colonialism by Sai Englert

- two excerpts from An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

- one excerpt from The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine by Rashid Khalidi

Find readings from all sessions here

Past/Future Inqlab Gatherings

August — Inqlab: Economic Displacement

September — Inqlab #3: Social Exclusion

October — Inqlab: Political Dispossession – U.S. Imperialism

About The Facilitator

Dr. SaunJuhi Verma is a Fulbright immigration scholar, former professor, published author, and a researcher-activist with fifteen years of experience working on race and immigrant rights issues within a transnational context. Dr. Verma pivoted out of academia to found and serve as Executive Director of Inqlab, a community think tank for critical research on modes of collective liberation. Much of her passion and energy are invested in excavating the surveillance/policing infrastructure and its impact upon migrant labor, displaced communities of color, and the establishment of a settler colonial nation state. Her time is shared between scholarly productions and building community efforts for empowerment through creative expression.

Dr. SaunJuhi Verma is a Fulbright immigration scholar, former professor, published author, and a researcher-activist with fifteen years of experience working on race and immigrant rights issues within a transnational context. Dr. Verma pivoted out of academia to found and serve as Executive Director of Inqlab, a community think tank for critical research on modes of collective liberation. Much of her passion and energy are invested in excavating the surveillance/policing infrastructure and its impact upon migrant labor, displaced communities of color, and the establishment of a settler colonial nation state. Her time is shared between scholarly productions and building community efforts for empowerment through creative expression.

Welcome to the Inqlab chat room where we Uproot Settler Colonialism and Re-root Ourselves. In the moments between our monthly community labs we will continue the momentum within the chat forum. Every few weeks a prompt will be shared on Mondays to enhance our understanding of settler colonial rule. Primarily, the space is for building a community of kindred spirits who are curious and committed to dismantling our systems of oppression.

But first, let’s get to know each other. Will you share the story of your name? Who named you? How were you named? Did you choose a name for yourself? Names are integral to our sense of self, yet cultural practices of naming vary significantly. Which traditions of naming have you experienced? What does your name tell us about your places of origin. Take this moment to talk with your family, friends, others who have helped shape your name.

As for me, my mother found my name in a book and loved it. She chose Juhi to be my initial naming. My Dadi, grandmother, on the other hand felt it was too short to be a real name. Dadi added Soun to my full name, it means golden. Since Juhi is Hindi for the Jasmine flower, my Dadi and mother essentially named me Golden Jasmine. More so, my last name shares all kinds of details about my background without any contribution from me. For those in the South Asian community, my last name identifies my region of origin, religion, native language, caste, and of course paternal lineage. Even before I open my mouth, my name shares an entire story of how I’m placed politically, socially, and within our collective history. What does the way you were named tell us about who you are?

Hi All! My name is Zarreen and my name means golden. My aunt found my name in the Quran and shared it with my mom and dad who really liked the name and thus it stuck! It took me a long while to really love my name because growing up no one ever said it correctly or pronounced it right (I even had a teacher in middle school who tried to tell me how to pronounce my name correctly! The nerve!) Anyways as I grew up and left my town I learned to love my unique name and how it represented both my Bengali culture and religion. I now find it empowering to take the time to gently correct people, particularly in a professional environment, when my name is spelled wrong. I’m excited to learn about everyone else’s name!

Hi there! My name is Farha and my mom named me after the Arabic word for joy/happiness. My parents were very grateful and happy that I had a normal delivery at the time of my birth because the doctor told them that there could be a possibility that I would be born with Down syndrome. Fast forward to my birth and I was born very healthy and happy (a full ten pound baby!!)

Even though I grew up in a very Indian-Muslim household, my Arabic name made me realize that religion has a huge impact on my family and that Islamic names are very common practice even in India. It’s made me realize the importance of knowing my familiar languages like Hindi and Urdu but also the importance of Arabic.

My name was given to me by my mom when she, my dad and family were living in a Thai refugee camp. At the time, my family had escaped the brutal Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia in the late 70s. I was born in the camp and having very little and escaping unimaginable conditions, the name my mom gave me meant ‘everything’ in Khmer. I’ll never be able to fully grasp the significance of this moment for them, given their overwhelming circumstances. But in my life, learning about that moment gave me greater clarity, energy, and purpose. In some ways, they’ve returned the favor to me.

My name is Anna. I recently changed my name because my family of origin does not accept me due to my identity. I kept Anna because unlike the patriarchal surname and middle name I had, it felt more like “mine”, especially now that I’ve had the privilege of choosing it. Funny enough, the name Anna came from a commercial my Mom saw when she was on drugs in the hospital before giving birth.

Hi everyone.I gave me my name -Cubby- when I was about 6. There used to be a program called the Micky Mouse Club that I watched. There was a girl whose name was the name my parents gave me. She had blonde shirley temple ringlets and acted all girly. There was a boy named Cubby and he played the drums and tap danced and got to do all the fun boy stuff so I decided I wanted to be Cubby. refused to engage unless you called me Cubby, including at school. So it’s been Cubby since then. I live in Bombay and recently with the advent of contact lists in phone I noticed that when I said my name was Cubby, Kabi was entered, which is the phonetical transliteration. I decided I liked that because it didn’t give a lot of information on place or gender. So when I am in the US I am Cubby and in India, I am Kabi. my email and social media IDs start with cubbykabi – which in India then turns into a song – or it can also mean sometimes.

I’ve enjoyed reading everyone’s comments and appreciate this forum and it’s insight. Please pardon me if I have written too much.

According to my childhood internet research: Clarissa is of Latin origin meaning clairvoyant or bright, an idea which I liked but couldn’t be certain of. It was also a very uncommon name so I didn’t like it as a child but appreciate it more in adulthood.

Given (first) names where I come from sometimes aren’t treated as sacredly as I personally thought they should be. They are often chosen to match the father’s or purely for how they sound so the same names are often repeated. Some try to make up names by combining the same sounds with new variations. For example, prefacing classic European male names with “De” or ending female names with “isha”.

In my youth I assumed it was a lack of thought or creativity but I wonder now if this was their subconscious way of creating a culture amongst a people who didn’t want to cling to the traditions of those who colonized them.

Now, knowing how difficult it is to legally change names it reminds me of how certain powers are perpetuated.

Do you think the way we describe and document things in America affect the strength of stereotypes and/or our progress toward decolonization?